Key Points

Preeclampsia is a type of high blood pressure that some people get during pregnancy. This condition can happen after the 20th week of pregnancy. In some cases, it can happen in the 6 weeks (about 1 and a half months) after giving birth.

Most pregnant people who have preeclampsia have healthy babies. If you're at risk for preeclampsia, your provider may want you to take low-dose aspirin during your pregnancy to help prevent it.

Signs and symptoms of preeclampsia include, blurry vision, swelling in your hands and face or severe headaches or belly pain. Call your provider right away if you have any of these.

If preeclampsia is not treated, it can cause serious problems, such as preterm birth and even death. You can have preeclampsia and not know it, so go to all of your prenatal care visits, even if you’re feeling fine.

What is preeclampsia?

Preeclampsia is a serious condition that can happen after the 20th week of pregnancy or after giving birth (called postpartum preeclampsia). Most people who have preeclampsia have dangerously high blood pressure and may have problems with their kidneys or liver. Blood pressure is the force of blood that pushes against the artery walls. An artery is a blood vessel that carries blood away from the heart to other parts of the body. High blood pressure (also called hypertension) can stress the heart and cause problems during pregnancy.

Preeclampsia is a serious health problem for pregnant people around the world. In the U.S., it affects about 1 in every 25 pregnancies. While most people who have preeclampsia have healthy babies, this condition can cause serious problems. People who have preeclampsia are more likely to deliver their baby too early (before 37 weeks of pregnancy).

Can taking low-dose aspirin help reduce your risk for preeclampsia?

Yes, low-dose aspirin (also known as baby aspirin) can reduce the risk of preeclampsia.

If you’re at high risk for preeclampsia and your provider recommends low-dose aspirin, they will let you know when to start it. It’s important that you take low-dose aspirin exactly as your provider recommends it. Don’t take more or take it more often than your provider says.

Low-dose aspirin can be started any time between 12 weeks (about 3 months) and 28 weeks (about 6 and a half months) of pregnancy until giving birth. It’s ideal to start before 16 weeks (about 3 and a half months) of pregnancy, but be sure to talk to your provider about what’s right for you.

Who is at risk for preeclampsia?

There are some things that may make you more likely than other pregnant people to have preeclampsia. These are called risk factors. Your prenatal care provider may want you to take low-dose aspirin if:

- You've had preeclampsia before.

- You’re pregnant with more than 1 baby (twins, triplets, or more.)

- You have certain chronic health conditions, such as high blood pressure, diabetes, kidney disease, or an autoimmune disease like lupus. An autoimmune disease is a health condition that happens when antibodies (cells in the body that fight off infections) attack healthy tissue.

There are other factors that can put you at risk for preeclampsia. Your provider may recommend low-dose aspirin if:

- You've never had a baby before, or it’s been more than 10 years since you had a baby.

- You’re considered obese and have a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or higher. To find out your BMI, go to www.cdc.gov/bmi.

- You have a family history of preeclampsia. This means that other people in your family, such as your sister or mother, have had it.

- You had complications in a previous pregnancy, such as having a baby who weighed less than 5 pounds, 8 ounces.

- You had a fertility treatment called in vitro fertilization (also called IVF) to help you get pregnant.

- You’re older than 35.

- You’re a member of a group that experiences health disparities and racism. For example, Black pregnant people are more likely to have preeclampsia than white people.

- You’re a member of a group that has a low socioeconomic status. Socioeconomic status is based on many things, such as a person’s education level, job and income. People in groups that have a low socioeconomic status may have less access to health care services, experience higher levels of stress, and have unequal access to resources.

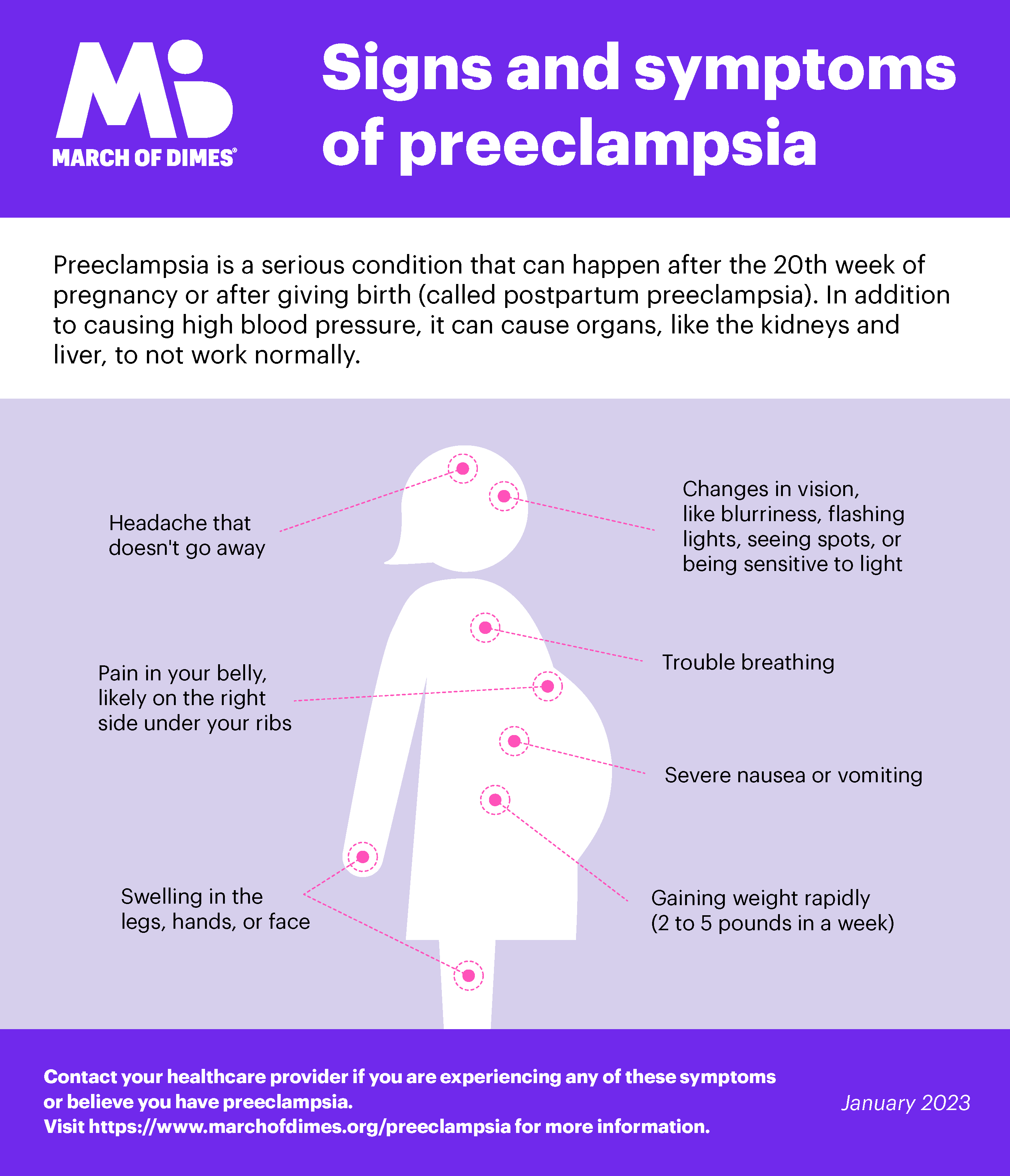

What are the signs and symptoms of preeclampsia?

Signs and symptoms of preeclampsia include:

- High blood pressure with or without protein in the urine. Your provider will check these during your prenatal visit.

- Changes in vision, such as blurriness, flashing lights, seeing spots or being sensitive to light.

- Headache that doesn't go away.

- Nausea (feeling sick to your stomach), vomiting or dizziness.

- Pain in the upper right belly area or in the shoulder.

- Sudden weight gain (2 to 5 pounds in a week).

- Swelling in the legs, hands or face.

- Trouble breathing.

Many of these signs and symptoms are common discomforts of pregnancy. If you notice any of these, call your healthcare provider right away. It’s possible to have preeclampsia and not have any symptoms. Go to all your prenatal visits, even if you feel fine. That’s the best way to detect preeclampsia.

How can preeclampsia affect you and your baby?

Without treatment, preeclampsia can cause serious health problems for you and your baby, and can even cause seizures or death.

Health problems for pregnant people who have preeclampsia include:

- Kidney, liver and brain damage.

- Problems with how your blood clots.

- Eclampsia or seizures.

- Stroke.

Pregnancy-related complications from preeclampsia include:

- Preterm birth.

- Placental abruption.

- Low birthweight.

- Postpartum hemorrhage.

Having preeclampsia can also make you more likely to have heart disease, diabetes and kidney disease later in life.

How is preeclampsia diagnosed?

To diagnose preeclampsia, your provider measures your blood pressure and tests your urine for protein.

Your provider may check your baby’s health with:

- Ultrasound.

- Non-stress test (NST). This test checks your baby’s heart rate.

- Biophysical profile. This test combines the NST to check your baby’s heartbeats with an ultrasound to check your baby’s movements and level of amniotic fluid.

Treatment depends on how severe the preeclampsia is and how far along you are in your pregnancy. Even if you have preeclampsia without severe features, you need treatment to keep it from getting worse.

How is severe preeclampsia treated?

If you have preeclampsia before 37 weeks, your provider:

- Will check your blood pressure and urine regularly.

- May ask you to collect your urine for 24 hours (this is called a 24–hour urine specimen) to check for protein.

- May want you to stay in the hospital so you can be monitored closely. If you’re not in the hospital, your provider may want you to have checkups once or twice a week.

- May ask you to take your blood pressure at home.

- May ask you to do kick counts to track how often your baby moves. There are two ways to do this: Every day, time how long it takes for your baby to move 10 times. If it takes longer than 2 hours, tell your provider. Another option is to count the number of times your baby moves in 1 hour three times a week. If the number changes, tell your provider.

- May recommend that you have your baby early if your condition is stable. This may be safer for you and your baby. Your provider may give you medicine or break your water (amniotic sac) to make labor start. This is called inducing labor.

How is severe preeclampsia treated?

If you have preeclampsia with severe features (this includes very high blood pressure), you will most likely stay in the hospital so your provider can closely monitor you and your baby. Your provider may treat you with medicines called antenatal corticosteroids. These medicines help speed up your baby’s lung development. You also may get magnesium sulfate to control your blood pressure and medicine to prevent seizures.

If your condition gets worse, it may be safer for you and your baby to give birth early. Most babies born to pregnant people who have preeclampsia with severe features before 34 weeks of pregnancy do better in the hospital than they do staying in the womb. If you’re not yet 34 weeks pregnant but you and your baby are stable, you may be able to wait to have your baby.

If you have preeclampsia with HELLP syndrome (high liver enzymes and low platelets), you almost always need to give birth early.

If you have preeclampsia, can you have a vaginal birth?

Yes. If you have preeclampsia, a vaginal birth may be better than a Cesarean birth (also called c-section). With vaginal birth, there's no stress from surgery. For most pregnant people with preeclampsia, it’s safe to have an epidural to manage labor pain as long as your blood results are normal. An epidural is pain medicine you get through a tube in your lower back that helps numb your lower body during labor to help manage contractions. It's the most common kind of pain relief during labor.

What is postpartum preeclampsia?

Postpartum preeclampsia is a rare condition. It’s when you have preeclampsia after you’ve given birth. It most often happens within a few days after giving birth, but it can develop up to 6 weeks after delivery. It’s just as dangerous as preeclampsia that happens during pregnancy and needs immediate treatment. If not treated, it can cause life-threatening problems, including death.

Signs and symptoms of postpartum preeclampsia are like those of preeclampsia. It can be hard for you to know if you have signs and symptoms after pregnancy because you’re focused on caring for your baby. If you do have signs or symptoms, tell your provider right away. Symptoms include headache, changes in your vision, swelling of hands and face and high blood pressure.

We don’t know exactly what causes postpartum preeclampsia, but these may be risk factors:

- You had gestational hypertension. Gestational hypertension is high blood pressure that starts after 20 weeks of pregnancy and goes away after you give birth.

- Your BMI is over 30.

- You had a Cesearean birth.

- You had preeclampsia in a previous pregnancy.

Complications from postpartum preeclampsia include these life-threatening conditions:

- HELLP syndrome.

- Postpartum eclampsia (seizures). This can cause permanent damage to our brain, liver and kidneys. It also can cause coma.

- Pulmonary edema. This is when fluid fills the lungs.

- Stroke.

- Thromboembolism. This is when a blood clot travels from another part of the body and blocks a blood vessel.

Your provider uses your blood pressure measurements, blood and urine tests to diagnose postpartum preeclampsia. Treatment can include admission to the hospital for magnesium sulfate to prevent seizures and medicine to help lower your blood pressure. You may be asked to monitor your blood pressure at home or to return in the days after getting discharged to recheck your blood pressure postpartum.

Last reviewed: April 2024